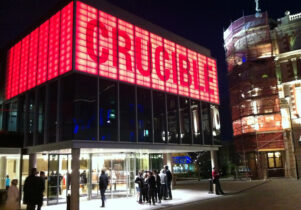

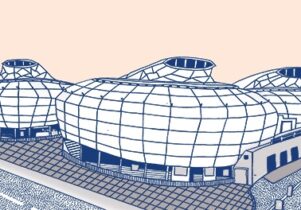

Park Hill Council Estate, Sheffield

Kathryn Hall

Sheffield’s Park Hill housing estate – a utopian architectural vision that lost its way and is now part of a long running Urban Splash led regeneration project.

When it welcomed its first tenants in 1961, Park Hill was a pioneer of social housing in post-war Britain. Replacing grime-ridden back-to-backs, it represented an upright utopian ideal of modern living, a clean slate for the communities it rehoused; it looked to a future free from the reminders of war and Victorian living. Park Hill’s flats and maisonettes elevated tenants above the land they’d previously crowded into, giving them the panoramic views, fresh air and space they could have only dreamt of in the past.

Park Hill put into practice some of the architectural theories that were circulating in the 1950s. Its architects, Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith, were young idealists, enamoured of Le Corbusier’s modernist Unité d’Habitation and his views on the social power of architecture. The idea was to keep the existing social structure intact, but transpose it into “streets in the sky”. For example, rows were named after the terraces they replaced and the decks were wide enough for milk floats and socializing. The design incorporated four pubs, a school, play areas and around thirty shops – it catered to the needs of a healthy society, all in one place.

Like so many utopian visions, the Park Hill dream didn’t last

Like so many utopian visions, however, the dream didn’t last. By the ’70s, public money for council housing wasn’t what it had been, inflation was rising and unemployment in Sheffield on the up as the spark of the city’s steel industry began to fade. Security became less of a priority, maintenance work too costly, and Park Hill’s reputation was severely undermined. Though relatively positive to begin with, public opinion on the development had always been divided. Rising instances of crime around Park Hill didn’t do much to win people over and, by the time it was Grade II* listed in 1998, many in Sheffield had a hard time seeing past this, to the building’s original sociological significance.

With redevelopment gradually getting under way from 2005 onwards, it remains to be seen what Park Hill’s future will look like. If the first completed phase is anything to go by, though, it’ll be bright and colourful. Apparently sharing some of the optimism of its original architects, property company Urban Splash have taken on the job of tapping into Park Hill’s potential and breathing new life into its raised rows. But to make their vision viable, Park Hill’s purpose will have to change, with a lower percentage of the completed estate going to social housing.

Despite its damaged reputation, Park Hill hasn’t failed to inspire passion. The most heartfelt defence of this hilltop curtain of concrete comes from its former caretaker, Grenville Squires. Turn on the TV in Weston Park Museum’s mock Park Hill kitchen and you’ll hear Grenville read his poetic ode to the place. It ends on an impassioned plea: “Replace the concrete, repair that crack / Then put the community spirit back / Make it a place we want to see / Please give Park Hill some TLC.” It seems that Grenville is about to have his wish granted.