Transit at Cultureplex

Tom Grieve, Cinema Editor

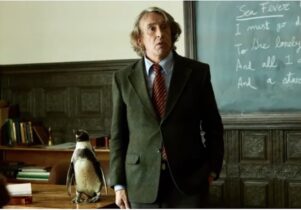

It takes a moment to adjust to Transit, the new film from Berliner Schule director Christian Petzold. The filmmaker wowed us in 2014 with Phoenix, a slippery riff on Hitchcock’s Vertigo starring Nina Hoss as a Holocaust survivor who returns to Berlin following facial reconstruction surgery. With Transit Petzold returns to WWII, sort of, as he adapts Anna Segher’s 1942 novel of the same name into an equally brilliant labyrinth. Franz Rogowski is Georg, a refugee in Paris who is in desperate need of transit papers. But this isn’t 1942, or at least it doesn’t look like it. Petzold films in the streets of contemporary France, his policemen are outfitted in up to date tactical combat gear and modern cars line the streets.

The main characters dress in a manner that is chronologically ambiguous though, they write letters and their passports are straight from the 1940s. Georg escapes from Paris to Marseille with the help of an underground resistance, but his ultimate destination is the safety of Mexico. In collapsing space, time and history, Petzold draws bold comparisons between Nazi-occupied France and the current migrant crisis affecting his native Germany, Europe and the world more broadly. It’s a risky approach and one which could have played out as a gimmick, but the effect is bewitching as we find ourselves lost with Georg; caught up in the folds of a dangerous and increasingly fluid situation.

In collapsing space, time and history, Petzold draws bold comparisons between Nazi-occupied France and the current migrant crisis

The films opening scenes in Paris see Georg sent to deliver a letter to a novelist named Weidel. He arrives at the writer’s hotel to find him dead, but takes a manuscript and keeps the letter. With the authorities closing in, Georg flees by train to the port city of Marseille where he is mistaken for, and takes to impersonating, Weidel and granted papers guaranteeing safe passage to Mexico via the USA. The embassies, harbours and cafes of Marseille are full of other travellers, with papers and without. Georg is far from the only one looking for a way out, and he spends tender moments first with the wife and son of a deceased comrade, then with a doctor and his girlfriend, Marie (Paula Beer). Transit slowly shifts from a thriller to a melodrama, with circles of deception bisecting ripples of genuine feeling and romance, all complicated by a situation in which there are simply not enough transit papers to go around.

It’s the kind of film that demands revisiting, not necessarily because the plotting is hard to follow, but in order to properly marvel at the structural complexity and the ease with which Petzold seems to handle it. As Georg, Rogowski manages the difficult task of depicting a desperate man on the run whose understandable instinct for self-preservation clashes with a desire to help those he meets in Marseille. It’s a remarkable performance in a remarkable film. Petzold’s deft, postmodern borrowing of Segher’s source pays off tenfold, as Transit successfully relates the humanity, desperation, frustration and fury inherent in the refugee experience, drawing stark parallels between the darkest days of the twentieth century and those in which we live.