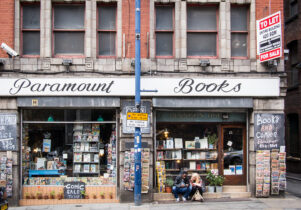

Now Showing Club x Bigger Than Life/ Shoot the Moon Right Between the Eyes at Old Bank Residency

Tom Grieve, Cinema EditorBook now

Shoot the Moon Right Between the Eyes

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

Graham L. Carter’s approach to moviemaking is refreshing. The Brooklyn-based director of low-budget independent film Shoot the Moon Right Between the Eyes embraces artifice, mood and all of the romantic possibilities of cinema with a style that’ll make you swoon. Presented at Old Bank Residency’s micro-cinema as a UK Premiere by Bigger Than Life and Now Showing Club, Shoot the Moon is a musical comedy about two conmen in a small Texan town. For structure, Carter borrows from James Joyce’s Two Gallants, whilst the music is courtesy of country singer-songwriter John Prine.

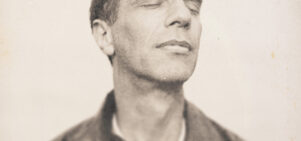

Vietnam veterans and seasoned outlaws Jerry (David Kendrick) and Carl (Sonny Carl Davis) have conned their way across the state of Texas. Jerry seduces wealthy women, whilst Carl, his partner in crime, keeps an eye on the money. Predictably, things go awry when Jerry falls for his mark, the wise and lovely Maureen (Morgana Shaw). Carl isn’t happy, but there are further complications in the form of a bumbling P.I. (Frank Mosely) who’s (not so) hot on their trail, having been set after the old boys by a previous mark.

Carter boldly (and correctly) trusts his ability to sweep the audience away with his lush, romantic vision.

It’s clear from the dedications that open Shoot the Moon (Eagle Pennell, Edward G. Ulmer, Frank Borzage and Jean-Claude Biette) that Carter is a filmmaker devoted to the medium. He films in the old standard, square Academy ratio, but the movie Shoot the Moon brings to mind is Francis Ford Coppola’s 1982 Tom Waits/Las Vegas musical One From the Heart. Whilst working with a smaller budget, Carter nevertheless delivers a musical comedy similarly set in a movie-world of neon and smoke. When Jerry and Maureen dance for the first time the world around them recedes, we’re left with faces, eyes and lips bathed in yellow and purple.

This is a film that recognises the power in making a big deal out of small moments. There’s a scene where Jerry and Carl come across a man sat out on his porch with a guitar singing the cowboy song “Streets of Loredo”. It’s almost a throwaway, but Carter lets the whole song play out, zooming in on Jerry’s face as we slowly realise that his new feelings might cause a problem. The knockout comes later though, in a duet of Prine’s “Maureen, Maureen”, where the director uses lighting to visually isolate his performers to an almost theatrical degree. In eschewing any pretence of naturalism, Carter boldly (and correctly) trusts his ability to sweep the audience away with his lush, romantic vision.