Peterloo at HOME

Jim Laycock

Tickets for the London Film Festival premiere of Mike Leigh’s Peterloo at HOME sold out in less than 5 minutes. It was the first time the festival was hosting a premiere outside of the capital and the event had generated some buzz in Manchester. Leigh’s film is the first big screen dramatisation of the infamous massacre of 1819, dubbed ‘Peterloo’ (due to scenes of bloody carnage compared at the time to the Battle of Waterloo), in which thousands of peaceful demonstrators were attacked by Yeomanry and government forces at St Peter’s Field, Manchester. The massacre left 16 dead and many hundreds seriously wounded. Ahead of the premiere, and in anticipation of the film’s general release, we spoke to multi-award-winning and multi-Oscar-nominated director and Salford native.

“It isn’t well known.” Leigh tells us of the events of Peterloo which led to a nationwide public outcry and began a movement which led to massive political and cultural reforms in Britain. The important place of the massacre within the British socio-political landscape — a vital moment in the fight for regional parliamentary representation, which would eventually come in 1832 — is indisputable, yet it is surprising just how little it is known and discussed in British historical discourse, especially here in Manchester. As Leigh says, “I grew up around this area and never knew about it. Even today a lot of the people working on the film, from people in their 20’s to my age who grew up Greater Manchester didn’t know about it either. It’s curious”.

The film was mostly shot outside of Greater Manchester, in various locations around the country that stood in for the pre-industrial revolution city (the film’s climactic massacre was actually filmed in Essex) but a great deal of care went into recreating Manchester on screen. So what does the director think about Peterloo being unveiled a stones throw from the location of the massacre? Leigh says,”It’s great, fantastic and more than important. People came from all over the place, Lancashire and would’ve walked past where HOME is. In the very spot we’re sitting in now (in the dining room of the Pinnacle/formerly Palace Hotel), when it all kicked off, people would’ve been here too. The troops that were lined up were mostly in St John St, just off Deansgate.”

The film spends a lot of its runtime carefully detailing the climate that led to the disastrous events at the St Peter’s Field demonstration, showing the contrast of experience between the land owning and political classes and the working class in the north, who bore the brunt of the economic fallout from the Napoleonic wars. The Corn Laws meant heavy taxation on grain which hit the poorest hardest and the changes brought about during the Industrial Revolution brought further uncertainty to a workforce already on the breadline. Meanwhile, London appointed magistrates administered the harshest punishments for the smallest crimes — but a swell of dissatisfaction slowly became a political movement for change.

Leigh analyses the minutiae of this movement with painstaking detail, through the experiences of dozens of characters on both sides of the divide. The challenge to represent these events accurately was evident and reflected in Leigh’s famously meticulous preparation. The research process began 3-4 years before cameras rolled, with historian Jacqueline Riding, enlisted to continue a collaboration started with Leigh’s 2014 film, Mr. Turner. How did he go about representing such a complex political situation on screen? Leigh says that “It all comes from the history books. Everything in the film emerged naturally from that history, I never had to contort myself to include anything.”

He goes on to describe a scene from the film, that to today’s viewer might seem absurd in its cruelty. In the sequence, one of Manchester’s government appointed magistrates sentences a man to death for a petty theft, but Leigh insists was based on real events, “These were actual cases, that were tried by those actual magistrates. We didn’t need to strain to include these things, they were all there, they happened.” Despite the events of Peterloo occurring nearly 200 years ago, there are parallels with contemporary life, whether it be political division, austerity, and even the important role of the free press — a detail not lost on Leigh. “As we started preparing it and through filming, it became increasingly apparent that this is all really relevant.” Were contemporary political events on his mind when he made the decision to make the film? “Yes, but for me they always are.”

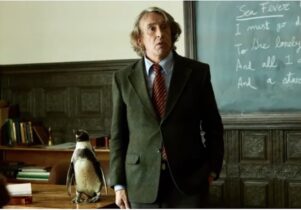

Peterloo is very much a Mike Leigh film, but there is an astonishing sense of scale that we might not expect from the director. Discussing his oft-documented method of improvisation Leigh tells us that “It was as much a part of this film as my others”, insisting that the larger canvas didn’t effect how he works, “For me, everything is interesting. People often say my films are mainly about character, but for me, they are about place too. Is making a film with hundreds of extras a departure? Yes. I’ve made lots of films with people arguing on staircases in suburban houses, but for me, it’s all the same. I’m interested in how people behave. This is just on a bigger scale.”

Leigh’s focus on character is key to making the film such an immersive and ultimately moving experience, but the construction and realisation of the large scale action sequences is jaw-dropping. The film opens on a young soldier seemingly stuck to the ground, the chaos of the Battle of Waterloo unfolding around him. It is a heart-stoppingly kinetic action sequence that wouldn’t look out of place in a Steven Spielberg movie. The film’s climax, the Massacre of Peterloo itself, is also realised with an overwhelming sense of scale and clarity. It was important for Leigh to convey the sheer size of the event, but also important is the sense of avoidable calamity in the decisions that turned demonstration into massacre, “It was chaos, a total mess. The deciding factor was General Bing deciding to go to the races (he delegated the management of the demonstration to someone far less qualified). It was a total shambles. It very quickly went wrong. I hope we got a sense of that on film.”

In creating Mr. Turner‘s stunning, textured palette, Leigh and his team drew from JMW Turner’s own paintings and period accounts. Peterloo employs a similarly well researched approach to its visual style and boasts another stellar contribution from Leigh’s regular DOP Dick Pope. One composition in particular, a meeting lit by candlelight, draws comparisons with the famous bridge scene in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. It’s an influence Leigh plays down though: “Funnily you should mention, we actually had a look at Barry Lyndon before Mr. Turner, but it wasn’t something we thought about for this film. The real answer, candles are how people lit rooms back then. It wasn’t for arty effect.”

In realising the film, Leigh stresses the importance of his producing partner Georgina Lowe, with whom he’s been working in various capacities for 25 years, since Naked (1993). Also familiar is Leigh’s uncanny knack for casting, which is spot on right the way through, and the film sees the return of many faces known to those who have followed his work. From small but significant cameos delivered by the likes of Marion Bailey (Meantime, Mr. Turner), Phillip Jackson (High Hopes) to the tandem of Martin Savage and Vincent Franklin, who shine as they reunite their memorable double act from Leigh’s Topsy Turvy. The director reserved special praise for Franklin’s sneering turn as a cruel, evangelical magistrate, “He really delivered the goods on this one. That kind of performance takes a lot of bottle.” Leigh also takes the time to hail the work of Neil Bell and Rory Kinnear, both working with him here for the first time.

Whilst it is a stretch to single out one particular performance in such a talented ensemble, Maxine Peake’s turn as working class matriarch, Nellie, resonates as she joins the great lineage of Mike Leigh heroines whose engagement with the pressures of life stand in stark contest with the male characters. Nellie’s line, “Times are too hard to lose hope” rings loudly today and our final glimpse of her face is a sobering, disarming reminder of the weight carried by working class women. Like many of his female characters, Nellie has a pragmatic optimism, standing as a pillar on which her family, workers and even weary travellers lean on in the film. Leigh elaborates, “The thing about Nellie, she had doubts, she’s not going to be seduced by any bullshit. But in the end, she’s still there (at the demonstration).”

Leigh is a famously ardent cinephile who grew up in and around Manchester and Salford before moving to London in 1960. We take the opportunity to ask him about what his experience of cinema-going was like, and how it has changed. “Where I grew up in Salford Central, you could walk to 14 cinemas without even going into town. Some were real flea pits that hadn’t been touched since before the war. They all showed 2 films in a programme that changed every Wednesday. So, if you wanted to, there was the opportunity to see a lot of films. The big difference to today…did I see a film before 1960 that wasn’t in English language? Never. It was mostly Hollywood: musicals, westerns, comedies and a lot of war movies. You also had the British stuff like Ealing and Powell & Pressburger. But, World cinema has been a massive part of my feast and continues to be.”

After a brief digression to discuss a mutual love of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s grand opus Berlin Alexanderplatz, we talk about the subject of London Film Festival (Leigh’s highlight: the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs) and how keeping up to date with new films is a big part of his routine: “I’ve spent the last week or so watching films all the time.” he says. Bringing things back to Manchester, we remind the director that this isn’t the first time he’s spoken about the Massacre of Peterloo in these parts. Of accepting an Honorary Doctorate from Manchester Metropolitan University in 2012, he tells us how he quoted the foul-mouthed miner bird, resident at the infamous Tommy Ducks pub, “I’m probably the only person in history to say “Fuck off cunt” in an acceptance speech for an honorary degree at any university, anywhere.” But his speech also spoke broadly and passionately of local history, including Peterloo and the Free Trade Hall — for Leigh, it is clearly important that Manchester’s rich cultural traditions are not forgotten.