Out of Blue at HOME

Tom Grieve, Cinema Editor

Carol Morley is the first to admit that an adaptation of a minor Martin Amis novella isn’t what was expected of her. But the Stockport-born film director behind Dreams of a Life and The Falling maintains that Out of Blue is the third in her “Dead Woman Trilogy” and views her work on the film as much as an act of character rescue as adaptation. At the centre is still Mike Hoolihan, an awkwardly named female detective (played here by Patricia Clarkson) charged with investigating the apparent murder of Jennifer Rockwell, a beautiful, acclaimed astrophysicist with a special interest in black holes. Morley spins her own yarn though, to the extent that she abandons characters, backstory and even Amis’ title (Night Train) for her own, more mysteriously evocative Out of Blue.

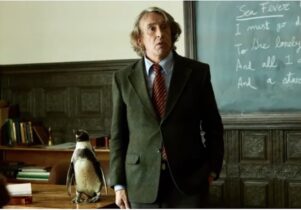

Set in present-day New Orleans and anchored by Clarkson, decked out in black leather and dark shades (one character jokingly references Joan Jett) as Mike, the film relies less on traditional noir beats than a haze of memory, dream and insinuation. Morley leans into the cosmological interests of the deceased Jennifer and boyfriend/colleague/prime suspect Duncan (Jonathan Majors), with a script that’s full of references to Schrödinger’s cat and stardust, supported by trippy visualisations. Meanwhile, masks emerge as a dominant motif and metaphor; a recurring symbol mirrored in the narrative churn as the central mystery of Jennifer’s death slips away to reveal a second – this one existential and rooted in historical horrors.

The rights to the source material had been optioned by the late Nicholas Roeg (Walkabout, Don’t Look Now) and offered to Morley by his son Luc. Indeed, there’s something of Roeg in the editing style, whilst cinephiles will notice further elements of David Lynch and at least one direct homage to Roman Polanski’s Chinatown. A score by English composer Clint Mansell (Black Swan, High Rise) adds further street cred. Out of Blue has sparked polarised reactions though, and it is easy to lose yourself in its dark avenues and dead-end side streets of the plotting. Get high enough on Morley’s dreamy mood and tough philosophising however, and you’ll float right on over such terrestrial concerns.