Jonathan Baldock: Touch Wood at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Katie Evans, Exhibitions Editor

Jonathan Baldock’s Touch Wood, a visually sumptuous and conceptually intricate exhibition, is coming to Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s Weston Gallery.

Baldock is renowned for harnessing myth, folklore and humour to create alternative realities rich in colour and texture. His storytelling and wit create all-encompassing environments that are paradoxically joyous and uncanny.

For Touch Wood, Baldock has created an entirely new body of work, combining his emblematic sculptures and textiles to create an immersive installation that reimagines queer and working people’s histories, making visible their traditionally hidden narratives.

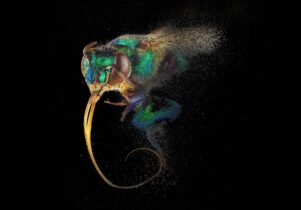

The exhibition is based on the fifteenth-century misericords of nearby Wakefield Cathedral. Misericords, also known as mercy seats, are protruding carved shelves on the underside of folding seats. Ordinarily concealed when seated, they are revealed when the seat is returned upright. They offered relief to medieval church-goers persevering through a long service or prayer and needing somewhere to subtly perch. Given how inconspicuous they are, it allowed the craftsperson greater freedom to choose what imagery to carve – nature and mythical beasts more often than religious iconography – offering an insight into the interests and visual storytelling of communities beyond the church.

The craftspeople also had a sense of humour. In Wakefield’s cathedral, there’s a misericord depicting a mischievous “tumbler” (a jester) bending over, trousers down, its exposed buttocks later covered by the Victorians with a modesty fig leaf.

As a queer and working-class artist, Baldock resonates with these historical craftspeople finding “pockets of joy” in expressing themselves, undercutting the church’s hold on creativity. Baldock’s own misericords are infused with colour, texture and folk imagery, enlarged to a scale that undermines their tradition of concealment, ushering them into the spotlight.

What would, in other hands, be anachronisms butting up against each other, are, in Baldock’s, a coherent body of work that deftly weaves several themes and timeframes.

Hanging textile panels form an embroidered architecture, with a circle of four panels at the heart of the gallery and others forming columns. These panels replicate a spiritual space, simultaneously a nod to the architecture of the church and to the drama and scale of the natural world.

And Baldock’s signature wit and humour extends to the exhibition’s title. Aside from the tongue-in-cheek innuendo, Touch Wood encourages a haptic interaction with the wooden carvings and nods to the ritual of superstition.

Visitors can expect a visually sumptuous and playful experience that explores how memory and creativity function in long-established structures, and leads us to ask, exactly whose version of history are we collectively preserving?