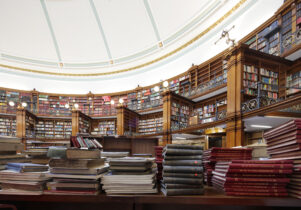

John Moores Painting Prize 2025 at the Walker Art Gallery

Maja Lorkowska, Exhibitions EditorVisit now

John Moores Painting Prize 2025

Always double check opening hours with the venue before making a special visit.

The North’s favourite painting prize is back this September, with 71 freshly selected paintings on display at Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery.

The John Moores Painting Prize showcases the breadth of contemporary painting from all around the country. There are large expressive canvases, figurative pieces, pastel landscapes, tiny and carefully detailed works, and everything in between. The exhibition gathers the subjects and techniques that contemporary painters are interested in, and with the sheer amount of work on display, there is something to catch everyone’s eye.

This year, the prize attracted 3,000 entries. At only 27, Ally Fallon became the youngest ever winner since the competition began in 1957, while Davina Jackson, Katy Shepherd, Miranda Webster and Joanna Whittle were the other four shortlisted artists.

Fallon’s painting If You Were Certain, What Would You Do Then? (2025) is difficult to describe – it appears to depict a semi-abstract interior in warm shades, with a patterned floor but its painterly language is fluid enough that it could be treated as a visual experiment, an attempt to push the boundaries of painting. Judge Louise Giovanelli described it as “a tightrope walk of a painting and there’s nothing quite like it in the show.”

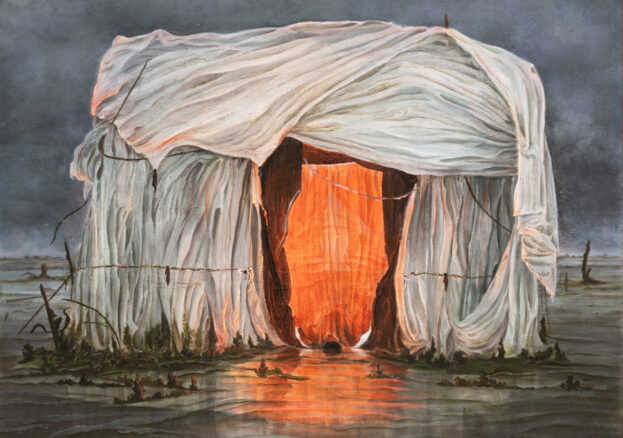

The other shortlisted paintings are no less intriguing. Joanna Whittle’s Darkened Heart (a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth) (2025) depicts a white tent emitting a warm orange glow, in what could be both a real or imagined watery landscape. Nothing here is certain but the aura is unique to Whittle’s style and her mysterious paintings of forest altars and circus-like structures.

Miranda Webster’s laid out (2024) is a narrow image of a young, dead tree. The artist purchased the tree from B&Q and left it to die on a bathroom towel, later depicting it in minute detail.

Katy Shepard’s Bedscape 2 (2025) is a softly-coloured image of the artist’s rumpled bedding with its folds and valleys becoming reminiscent of an otherworldly landscape. The duvet appears inviting, with the morning rays of sunlight, or perhaps a nightlight, casting gentle shadows. Is this a celebration of an ordinary domestic moment or the result of insomnia?

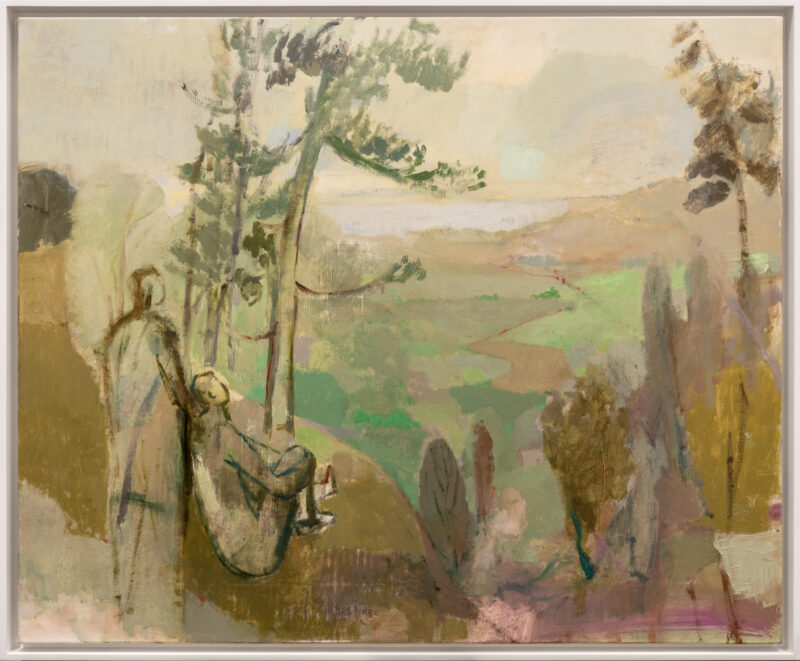

Davina Jackson’s Just Like It Was (2025) is a work that could’ve been made this week or 100 years ago. The artist depicts a landscape with two contemplative figures in loose brushstrokes and muted colours which, like many of her other works, has a timeless quality. Memory, longing, and introspection are easily discernible themes in the piece.

The John Moores Painting Prize is one of the most important art prizes outside of London (and in general) and we’re very lucky to have it on our doorstep. It’s worth seeing for this reason alone, but the range and quality of this year’s works make it especially exciting.