Bigger Than Life Presents: The Magnificent Ambersons (35mm) at HOME

Tom Grieve, Cinema Editor

Orson Welles has been in the news lately thanks to the completion and release of his final film, The Other Side of the Wind. This wild, experimental mockumentary was finally completed 33 years after Welles’ death thanks to the endeavours of his friend and collaborator Peter Bogdanovich and producer, Frank Marshall. The film is dizzying; constructed partly from the perspective of a camera-wielding cohort of film journalists at a screening-party and partly of footage from a handsomely parodic film-within-a-film. In other words, it’s pure Welles: bold, innovative and produced under compromised conditions.

The director might be best known as the wunderkind who wrote, directed and starred in Citizen Kane whilst still in his twenties. He’d go on to direct a dozen more films, but his career was stuttered and interrupted as studios meddled and financing fell through. Depending upon who you listen to, Welles would reach higher points than Kane in subsequent films. One contender is the 1958 noir Touch of Evil with Charlton Heston, which glitters despite its grubby depiction of police corruption — Welles wasn’t allowed final cut, though. Some prefer the freewheeling cheekiness of his 1973 low-budget docudrama F for Fake — but his talent deserved a bigger stage.

In many ways the film which best encapsulates the brilliance and the tragedy of Orson Welles is his 1942 follow up to Citizen Kane, an adaptation of Booth Tarkington’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Magnificent Ambersons for RKO. Reports are that some early viewers felt the film better than Kane, but it ran over two hours, and besides, were war-time audiences ready for a mammoth tale of woe and misfortune? Europe was in flames, could they really be sold on a rich epic about the slow melancholy of industrialisation? Welles departed for Brazil on diplomatic work and in his absence, RKO chopped 45-minutes of Ambersons and filmed new scenes, including a more up-beat ending.

The director reacted with sorrow and fury, and even attempted to film another ending thirty years later, only to be foiled again by finances. The original ending is lost to history — not that there aren’t those who hold out hope that the missing reels will turn up in a vault somewhere — yet The Magnificent Ambersons remains one of the best-loved films ever made. It placed 81st in Sight and Sound’s list of The Greatest Films of All Time and clocked in at number 11 on BBC’s countdown of the 100 greatest American films, where esteemed critic Molly Haskell noted that “While most critics would vote for Citizen Kane as the greatest American film, or certainly director Orson Welles’ best film, The Magnificent Ambersons has always moved me more deeply.”

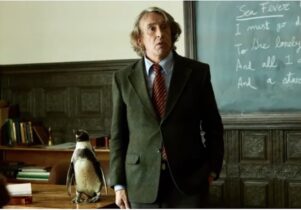

It’s a sentiment Haskell shares with many. Ambersons opens at the beginnings of the 20th century in the midwestern city of Indianapolis, as the soothing tones of Welles’ own narrator explains the grand shadow cast by the titular family, and the ordered pace of a way of life that is about to be severely disrupted. Joseph Cotton stars as Eugene Morgan, a young man who ruins his chances with Isabel Amberson (Dolores Costello) when he publicly embarrasses her. Time passes, and while both move on to have children separately — Eugene a charming daughter named Lucy (Anne Baxter), and Isabel a spoiled terror called George (Tim Holt) — circumstances bring them together again some years on.

Welles weaves an elegant tapestry of missed connections, misplaced longings and heartbreaking romance. As Eugene’s interest in the automobile business sets him on an upward trajectory, marching industry spells trouble for the Ambersons’ old money. Pride and propriety play their part as the Ambersons’ vast, foreboding mansion plays stage to a drama of merriment that slowly sours. Even allowing for its truncated form, few films can lay claim to such an exquisitely wistful account of the passing of the years, including a wintertime set-piece which sumptuously encapsulates the film in miniature.

As with Kane, Welles employs low angles and deep-focus cinematography to great effect, amplifying his themes in shadow and light. Expressive close-ups of faces help set the tone whilst we’re swept through an extravagantly staged ball (“the last of the great, long-remembered dances that everybody talked about”) on a gust of wind. The Magnificent Ambersons will always exist with a caveat, but the film we have today is more than worthy of adoration. Local cinema initiative, Bigger Than Life present Welles’ masterpiece with a short introduction at HOME from a 35mm print delivered courtesy of the British Film Institute.