Beautiful world, where are you? at Tate Liverpool

Sara Jaspan, Exhibitions Editor

International contemporary art festivals are generally, by their very nature, relatively diverse in terms of the range of countries from which the artist line-up is drawn. But to what degree does this reflect the multiplicity of cultures, nationalities and identities belonging to each nation or place? And what histories shape the story behind this?

For Liverpool Biennial’s 10th edition, Tate Liverpool’s top floor will be dedicated to a group of artists predominantly originating from America, Australia and Canada. The work deals with the complex interactions of race, nation and culture in settler societies (communities living in colonised areas) and the often-violent legacies that accompany them – a story Liverpool does not shy away from acknowledging its own historic part in.

Descendent of the Bidjara Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples of Central Queensland, Australia, Dale Harding presents a striking new wall-based work inspired by the rock art and stencil techniques of his ancestors, rendered in Reckitt’s Blue – a dye and optical whitener that was produced in the UK and travelled along the colonial frontier to the laundries in Australia where Harding’s mother worked.

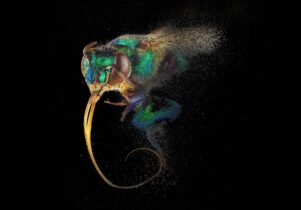

A series of drawings by Annie Pootoogook chronicle the everyday events of modern life in the small community of Kinngait; injecting a degree of realism into our notion of Inuit communities. Duane Linklater’s sculptures draw upon the fur trade as a way of not only addressing issues of cultural loss and social amnesia, but also reflecting on the very nature of exploring indigenous traditions within a European institutional context. And Brian Jungen’s dramatic Cheyenne-style headdresses, carved from the soles of Nike trainers, comment on a long history of conflict and the lingering effects of colonisation, whilst signifying the strength and pride of indigenous people today.

Elsewhere, Joyce Wieland’s subversive political film Rat Life and Diet in North America (1968) – starring a band of revolutionary gerbils – highlights America’s role as an oppressor state; and a sculpture and performance-based installation by Kevin Beasley employs symbols of state control, such as NATO-issued gas masks, to evoke individual and collective acts of protest, power and protection.

While you’re at Tate Liverpool, make sure you also catch Haegue Yang’s hybrid, multi-sensory, environment in the downstairs Wolfson Gallery, which deals with modern notions of ‘paganism’ and folk tradition.

Check out the rest of our guide to Liverpool Biennial 2018 here.