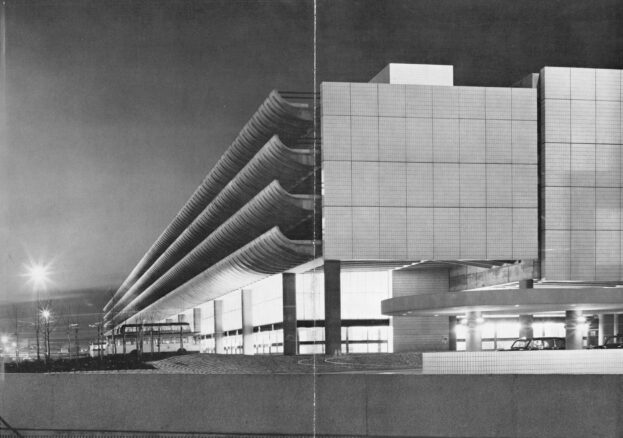

Beautiful and Brutal: 50 Years in the life of Preston Bus Station at Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library

Sara Jaspan, Exhibitions Editor

A monolithic, space age structure positioned almost in the very centre of the modest-sized Lancashire city, the Preston Bus Station is a remarkable site to stumble across – arrive at or depart from. It was the largest of its kind in Europe when it was first built in 1969, the same year as the moon landing. 50 years later and the station is still in active use – after a protracted, bitterly fought campaign led by local citizens, artists and architects to save it from demolition, winning it Grade-II status in 2013. Today, it is one of the 50 winners of the RIBA National Awards 2019 and its renovation has been longlisted for the ‘UK’s best new building’ RIBA Stirling prize, announced in October. It has also inspired numerous artists, filmmakers and photographers over the years, including Shezad Dawood and Nathaniel Mellors. Yet the concrete, Brutalist icon still continues to divide opinion; a classic example of Marmite architecture.

To celebrate its half-centenary, the Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library and Preston-based curatorial partnership In Certain Spaces are staging an exhibition of art and artist interventions, films, literature, rare archival material, collections, and related objects presented throughout the Harris and the station itself. This will run alongside a complimentary programme of talks, tours and workshops contextualising the social architecture of the building and its role in the city.

Designed by local architects, Building Design Partnership, the spectacle of the building is truly remarkable, but its social dimension is just as much what makes it special. The exhibition’s curator Charles Quick has described its internal spaces as cathedral-like, while the British writer, broadcaster and architecture historian, Tom Dyckhoff, has written of the building: “I think architecture is at its most meaningful and heroic when it celebrates like this the seemingly ordinary and everyday bits of time that connect us all.” Brutalism gained traction in the 1950s and 60s partly as a relatively inexpensive approach to construction in an economically depressed post-war Britain, yet it is was also underpinned by forward-looking, socially progressive intentions. Amidst the largely corporate, soulless new buildings that increasingly dominate our cityscapes, this internationally significant work of mid-century architecture seems well worth returning to and celebrating.