Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes at The Hepworth Wakefield

Sara Jaspan, Exhibitions Editor

Until very recently, Alina Szapocznikow remained a relatively overlooked artist outside of Poland. Yet, in the last five years she has risen to widespread international acclaim, becoming the focus of several major survey exhibitions at galleries such as MOMA in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Today she is increasingly considered to be one of the most important artists of the 20th century, and is about to receive her first major UK retrospective at The Hepworth in Wakefield.

Human Landscapes explores the artist’s idiosyncratic treatment of the human body, informed by the tumultuous social, political and personal events of her life. Szapocznikow was born in Poland in 1926 to a non-practicing Polish family. At the outbreak of WWI, aged 14, she was interned in the ghetto of Łódź, before than being transferred to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belson. It was during the unimaginable horror of these experiences that her fascination with the human form began. By the point of liberation in 1945, she was committed to becoming an artist.

From Poland, Szapocznikow moved to Prague and then Paris to study sculpture, where she received a traditional, figurative style of training. It was not long before her practice evolved into the kind of bold rearticulation of the human form that dominated the rest of her career. We see this in early works such as Monstrum (1957) or ‘Monster’, in which an ossified figure reminiscent, of the Pompeii casts, seems suspended in a state of writhing pain. By 1961, Naga (or ‘Naked’) shows a strangely elongated and deformed woman, whose enlarged head and torso seem painfully supported by a skeletal neck, misshapen spine and mismatched legs.

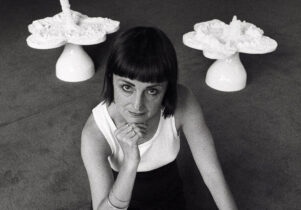

Perhaps her most original work began when Szapocznikow started making casts of her own body and experimenting with materials that ‘chartered a new language for sculpture’. These pieces combined everyday objects such as lamps, cushions or ashtrays, with fragmented, often illuminated body parts, such as her lips, buttocks or breasts. They show the influence of Surrealism, Pop Art and Nouveau Réalisme upon the artist, yet remain entirely idiosyncratic.

Szapocznikow’s most touching body of work, however, is probably Herbarium (1972), which draws upon her experience of being diagnosed with cancer, a disease which she battled with for the rest of her life. The series comprises of several flattened latex casts of her own body and young son’s, and has been described as the artist’s last gesture. The figures have an emptied, diminished quality to them; their two-dimensionality reminiscent of the way flowers might be preserved between the pages of a book.

Bringing together over 100 of Szapocznikow’s works, including a selection of drawings, which have rarely been publicly displayed, Human Landscapes looks set to provide a powerful reflection on what it is to be human, what it is to inhabit a body in this world, and all the strangeness attached to that.

Updated:

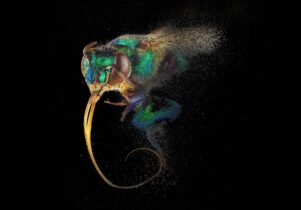

Szapocznikow’s Bird (1959) – a work once considered to be lost – will now be displayed for the first time in over 57 years as part of the exhibition.

Bird (1959), is part of a series of late-1950s works in which Szapocznikow took inspiration from the natural world and animal forms. Unfortunately, many of Szapocznikow’s works have been lost or destroyed, in part due to the experimental materials the artist used. Until 2016, Bird was amongst a list of pieces by the artist that were considered lost. The significant sculpture was found in the outhouse of an art collector in upstate New York and sold at auction to a private collector from Warsaw who wishes to remain anonymous. Bird has not been seen since its last public display, in 1961 at the Gres Gallery, Washington.