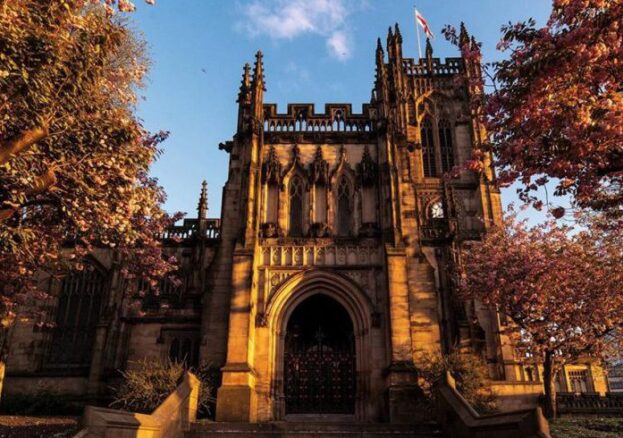

Manchester Cathedral

Susie Stubbs

If Manchester Cathedral could speak, it would have a few tales to tell. Of course it would – it dates back to the 1400s. Since then the place has outlived various attacks: during the Civil War, by overenthusiastic 19th century builders wielding Roman cement, by the Luftwaffe, and, in 1996, by the IRA’s behemoth bomb.

Not only has it survived these assailants, Manchester Cathedral, illustrated for us by Simone Ridyard, is now looking better than ever, thanks to a £2.3m redevelopment that has included the sort of under floor heating that makes it the greenest cathedral in Britain. And it withstood its latest assault (possibly) thanks to what the builders found buried beneath the stone flags they dug up in order to install this new system. Because what lies beneath Manchester Cathedral, like so many ancient places of worship the length and breadth of the British Isles, are bodies. Lots and lots of bodies.

Manchester Cathedral is, according to the Pevsner Architectural Guide, “one of the most impressive examples in England of a late medieval collegiate church”, and the building that stands today does so on the foundations of a much older house of prayer, one that dates back at least to the 13th century. It became medieval Manchester’s most important building; way back then, if you were someone who was anyone, the cathedral grounds would be your chosen place of eternal rest. So when the original floor was raised for the cathedral’s eight-month restoration a few years back, it exposed the numerous human remains, and several lead coffins, of Manchester’s once great and no longer good.

It was this sight that met two would-be robbers one dark Manchester night. Seeing the cathedral deserted, the pair smashed a window, clambered up and were about to go inside when – so the story goes – they spotted a glint of moonlight on bone. Human bone. And not just one bone, but dozens, hundreds, a series of bodies up to 600 years old that were in the process of being reinterred elsewhere in the cathedral. It was enough to make the miscreant pair rethink their options; they legged it.

This explanation makes for a good story, though the fact that someone tried to break in – and caused £20,000-worth of damage to a stained glass window – is true. But whether or not it was the skeletal remains there scattered that put the thieves off, it’s a tale that sums up the tumultuous life of a building that has for so long been at the centre of the city. Open all year round, and now a toasty warm venue for worship and music events alike, this is a medieval monument to all of Manchester’s saints and sinners – the past and present, the dead and buried and, occasionally, the breaking and entering kind.