Chetham’s Library

Andrew Anderson

Chetham’s in Manchester is the oldest surviving public library in the country – and the esteemed ancestor of Central Library.

Central Library get all the pomp and praise, doesn’t it. But while it may currently be the most prominent book repository in Manchester, it’s hardly the oldest. That title belongs to Chetham’s Library, a medieval marvel that is the nation’s most ancient lending archive of books, maps and photographs.

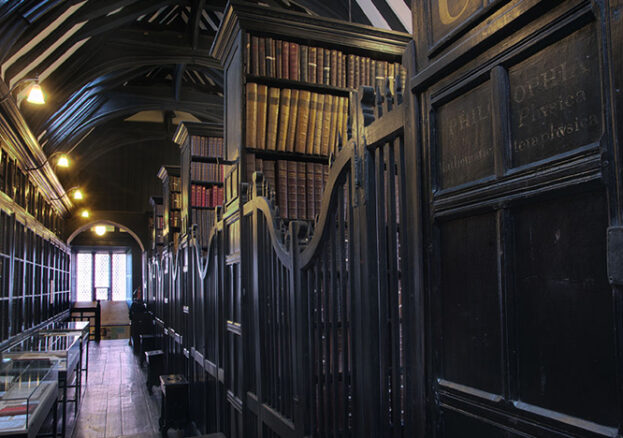

Finding Chetham’s is a bit like uncovering a lost relic in your back garden; the building is hidden away between Manchester Cathedral and the school that shares its name. From the first impression, it conjures up a sense of mystery and wonder: entry is gained by pressing a bell on a gnarled wooden door studded with iron bolts. Once inside, the serenity of the interior is exceptional even for a library. The almost-black wood of the beams and bookcases, the gold-lettered, Latin labels and the beatific expressions worn by the persons in the portraits combine to create an atmosphere of complete calm. It’s like stepping back in time.

Which, in a way, you are. The library was founded in 1653, which is old enough – but the building dates back to 1421 and once housed the nearby cathedral’s collegiate. Built with funds bequeathed by prominent businessman Humphrey Chetham, its mission was to assist “scholars and others well affected”. This, at the time, meant loading the shelves with a headache-inducing mix of literature, law and theology. The books are kept in imperious rows – originally they were chained to the walls to prevent theft – and their dark leather spines form an intimidating intellectual phalanx. Just off from the main shelving area is a resplendent reading room, brighter than the bookshelves and lined with those peaceful portraits. It’s the perfect place to quietly contemplate the library’s serious tomes.

The result of all this intellectual rigour was that Chetham’s Library became the place to be, if thinking was your thing. It is here that Marx and Engels researched much of the material that would inform their world-changing works (including the Communist Manifesto); Chetham’s is now something of a Mecca for left-leaning tourists. But while it might be ancient, Chetham’s is no fossil. It continues to be an active library, one that constantly adds to its collection. The focus now is on local history and donations, with cabinets of curiosities lining the corridors. Diary entries from Manchester’s second bishop, James Fraser (whose statue can be seen in Albert Square), are displayed in one, while the next is filled with books on African Nationalism (Manchester also played its part here, hosting the historic fifth Pan-African Congress in 1945). Yet another documents the decline of Free Trade Hall. It is just the sort of curatorial touch that you want from a library like this, offering a smattering of the interesting and unexpected.