Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections

Susie Stubbs

Victorian ephemera? Check. Artists’ books? Check. It may be small, but this is one Manchester museum that has more than a few treasures up its sleeve.

Some things are kept hidden away. Kept behind closed doors, marooned on dusty shelves, “archived” for so long that no one remembers they exist. You could blame private collectors. You could blame government cuts and the slow closing of Britain’s library doors. Or you could quit moaning and discover some of the lesser-known museums and archives, places that contain objects and artefacts that are not only incredible for the fact that they exist at all, but for the fact that you can go in and have a look pretty much whenever you like.

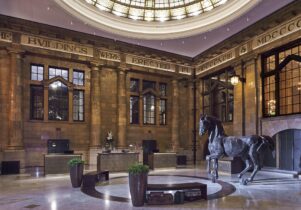

One such place (we hesitate to use the hackneyed phrase “hidden treasure” – oh, OK: hidden treasure) is Manchester Metropolitan University’s Special Collections archive. To our deep and possibly permanent shame, we didn’t know anything about it until a friend took us to one side not long ago and whispered its existence into our ear. Tucked inside a fairly nondescript university library off Grosvenor Square, this tiny museum has its origins in the Manchester School of Design (the precursor to Manchester School of Art); today’s archive includes books, prints, objects and ephemera that have been collected over the course of 175 years.

It is a million miles from the roaring traffic of the Oxford Road visible from its windows

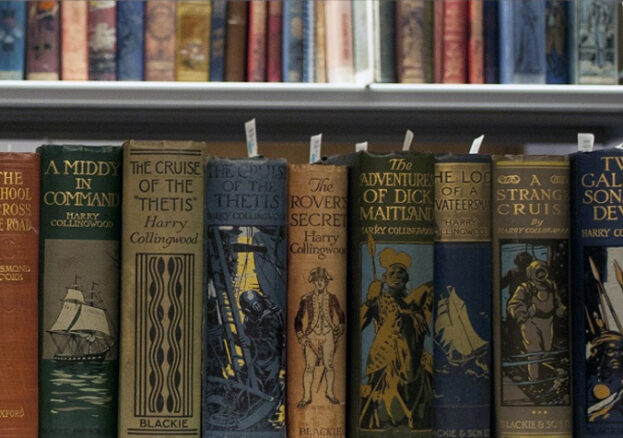

Everything contained within relates in some way to the students and academics who have called the various incarnations of MMU their scholarly home. Its glorious Children’s Book Collection, which spans 10,000 books and two centuries, was originally amassed as a resource for trainee teachers. Now, the heavily embossed and illustrated tomes are used by social historians interested in how attitudes to children have changed over the years, as well as by art and design students. Close by are some 2,500 artists’ books (the largest publicly accessible such collection outside London, fact fans), around 1,300 photographic negatives belonging to the former Cotton Board, Colour Design and Style Centre (a centre designed to raise the style bar within the post-war British textiles industry) and a wonderfully-titled collection of Victorian Ephemera.

This latter collection is a delight. It features 276 albums and “commonplace books” once owned by Victorian and Edwardian women and collected by former city councillor Sir Harry Page. He stumbled across them in the dusty corners of second hand bookshops, unloved by book dealers who in turn had only encountered them as part of job lots and house clearances – and thus saw little value in them. “They are scrapbooks containing watercolours, poetry, prose, pencil sketches, postcards and things cut out of newspapers,” says MMU Special Collection’s Louise Clennell. “We don’t know a great deal about them but they’re fascinating. They were sometimes made by one woman and other times a group of women, and passed from friend to friend. They were made to be seen but we’re not entirely sure what purpose they served.”

The books were perhaps part diary, part records of social aspiration (who hasn’t ripped things out of magazines that they liked the look of?), but Page’s collection has had an unusual legacy. “A woman called Laura Seddon went to a talk by Sir Harry about his collection and was so inspired that she decided to start her own,” says Clennell. “She went on to amass 32,000 Edwardian and Victorian greetings cards.” You can probably guess who now owns those cards, of which one in particular stands out: Britain’s first commercially-produced Christmas card. Which must have been some find.

There is much else in this museum and, with the university still actively collecting, the promise of more to come. But we like MMU’s Special Collections not only for its books and artworks. We like it because it is a quiet, scholarly sort of place. It is a million miles from the roaring traffic of the Oxford Road that’s visible from its windows. We like it because, for all its stillness, it is open to anyone with a passing interest. Sit inside and listen close. You’ll hear, along with the turning of pages, the murmur of history. Listen again and you’ll hear the thrum of new ideas a-whirring. This is one place where the doors have been left wide open.